Testing the classics: A Time Management Experiment: Time Blocking

Tuesday, June 2, 2009 at 9:45AM

Tuesday, June 2, 2009 at 9:45AM Nothing beats project anxiety like a plan. -- me :-)

You know me - I love experimenting on myself almost as much as on you. Or my clients. Kidding aside, I've studied many, many techniques to manage ourselves as we work, and a classic on is time blocking, AKA time mapping (see [1] for more). It's a simple idea: Schedule regular chunks of time with yourself for important tasks. The experiment I've tried for the last few weeks is applying it to three largish projects coming up (higher education workshops) with a relatively short timeline (less than a month). The advantage is it forced me to make steady progress on projects to prevent last minute scrambling, stress, and failure. The result: Worked great!

Following are the details, along with a few rules and caveats when time blocking.

(Updated 2009-06-08 to remove confusing project plan image.)

Planning and estimating

My first step was to get my head around all the work I'd committed to. The three workshop projects ranged in complexity from updating an existing full-day one, through adapting one for a shorter program, to creating a brand-new 90 minute one from scratch. I applied the planning ideas I'm developing (see Simple Project Planning For Individuals: A Round-up) and came up with the number of hours needed per project: 8, 12, and 18 hours, respectively. I tried to be conservative in my estimates, but ultimately only time would tell (uncertainty is a function of experience).

I then calculated the number of days available for each project from the day I started: 15, 24, and 19 workdays, respectively. Thus, to stay sane and on-target I needed to spend the following time every day for the next four weeks: 1/2 hour/day, 1/2 hour/day, and 1 hour/day. In other words, because of my (happily) agreeing to take on the jobs, I'd committed to working on these three projects 2 hours EVERY DAY. That was a shock.

Implementing

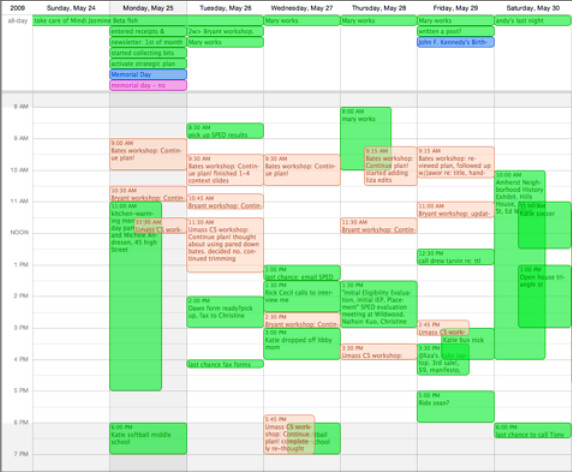

The next step was to simply create repeating entries in my calendar for the three blocks. Here's a screenshot from iCal for a typical week. (Note: Not all client work is shown in this view.) What you should focus on is the orange chunks.

You'll notice a couple of things. First, while they were all initially scheduled for the same time each day (in the morning - my prime time), you see that they've been moved. This was the first thing I learned - my life is unpredictable and varying enough that planned times don't always meet reality. So I adapted by negotiating with myself and pushing them down. I'm sure you see the possible problem: Pushing them completely off the bottom, i.e., not getting some done. I found I was consistently able to honor my commitment to myself (a zero tolerance rule), but this meant working late some nights - part of the deal of being a self-employed parent.

One novel thing I did that was helpful was using each block as a project accountability record. I did this by simply editing each appointment after finishing it by adding a short description of what I got done. This kept me honest. This little record-keeping didn't replace my full project plan. Like all my projects, that was captured and tracked in each project's outline.

Finally, if when I was deep in the flow I extended the time beyond what I'd allotted. The rule, though, was no borrowing from the others! This information was useful in after-action project analyses, esp. in answering, "How did estimated and actual compare?"

Wrap-up, Questions, and Challenge

Though I've tried smaller versions of this, overall the experiment validated this approach, and I'll continue recommending it to clients.

I'm curious: Have you (or do you) used this for yourself? For what projects does it work best? What have you learned that you'd like to share?

If you haven't yet tried time blocking, I'd like to challenge you to give it a spin on your next new project. Call or email me if you'd like help. I'd love to hear how it goes. Cheers!

References

- [1] See Time Design ("consistently setting aside time for high priority activities") or Julie Morgenstern ("allotting specific spaces in your schedule for tending to the various core activities of your life").

Reader Comments (10)

Matt, I can't really read/review the schedule or accountability matrix. Have you got a better image. I'm interested in how you documented the "time blocks", and the associated journal results in the accountability matrix.

I've been experimenting myself with "time blocks". Mainly on smaller projects that are not mission-critical. I'm noticing that my results vary and I'm trying to better understand when I'm the most productive with relationship to the context. For example, what is the best time to block for analytical, best time for creative, etc. Still grappling with an answer, but I've gained a better understanding of when I might best undertake a certain activity. An example is exercise time. I just can't do it in the afternoon and evening. I've tried and it just doesn't work. So if I don't start the day running (literally), then running isn't in the mix for the day. So' I'm blocking time for this activity as a must. This appears to be different from other activities that are getting blocked at different times for the purpose of experimentation.

Thanks for the post. It's been awhile. Hope all is well and wishing you continued success.

With regards,

Davey Moyers

Hi Davey. I really appreciate your comment. It's been a little quiet around the IdeaMatt lately...

Matt, I can't really read/review the schedule or accountability matrix. Have you got a better image.

Sorry about that, Davey. I intentionally blurred them to respect client privacy. I was hoping the pattern of how the blocks (orange) fit in among the appointments (green).

I'm interested in how you documented the "time blocks", and the associated journal results in the accountability matrix.

I like your expression, "accountability matrix." It took a few days for it to sink in. The comment within each block is a short summary of what I accomplished during it, which is what I think you mean. The second image is just a screen shot from my editor, with the point being that the short block comments weren't where I stored project plans or detailed journal.

what is the best time to block for analytical, best time for creative, etc. ... I've gained a better understanding of when I might best undertake a certain activity.

This is great work, Davey! Very TTL - have an idea (Think), experiment with it (Try), then form conclusions and adjust (Learn). And repeat. Good modeling for me - thank you.

An example is exercise time.

Great example. In my case my mood plummets around 2pm, so morning time is project time for me. I exercise in the afternoon.

different from other activities that are getting blocked at different times for the purpose of experimentation

Is it that you've done the experimentation with exercise have something that works, but you're still in process with the others?

Excellent, excellent, excellent!

This experiment really effectively pulls together techniques you’ve discussed in a disaggregated way in the past – estimating time required for a project; measuring actual vs. estimated time; keeping a journal of your progress; after-action reporting; outcome-based planning. It’s extremely helpful to watch you lay each layer in place and watch you fit each piece together.

You were obviously very rigorous in your execution: outstanding!

For me, the combination of a large, multi-faceted project with a deadline is a source of anxiety and resistance. I’m used to breaking these kinds of projects down into small parts, but I don’t often go farther than saying, “let’s do this a little at a time.” (Reference Robert Maurer here. Maurer makes the argument that from small steps, new habits emerge and lots of work gets done (eventually) – but the mechanism is mysterious and ambiguous, and the endpoint is not really open to contemplation. Your method, on the other hand, is satisfyingly concrete, specific, goal-oriented and transparent.) Those additional steps – estimating total time, apportioning it by days available, scheduling each part explicitly in your calendar, protecting that time in your day – make all the difference. Without these steps, the deadline can still wreak havoc.

I particularly like this observation: “I'd committed to working on these three projects 2 hours EVERY DAY. That was a shock.” This reminds me of my own shock (and dismay) when I first started GTD and assembled a complete list of my projects: no wonder I felt overwhelmed all the time. But, apart from the important emotional understanding, you’re teaching an important practical lesson: there may be more work here than you think – there’s almost certainly never less – so it pays to think in an organized way about it from the start.

As a building contractor, I’m in the habit of estimating time requirements for almost everything I do on the job, on a daily -- sometimes hourly -- basis. Breaking huge on-site projects into component parts, working backwards from deadlines, constantly re-orienting and re-planning around unexpected developments – this all comes very naturally to me in that environment. But I treat the office-based paperwork components of my job in a much more relaxed manner, with predictable, high-anxiety, deadline-based unhappiness.

Thanks for sharing this, Matt. You’ve really driven these lessons home.

A last thought that occurs to me. This experiment is based on one way of working: break big projects into small projects, and work in short blocks of time. In this model, flow is serendipidous -- useful if it shows up, but not necessary. There is another school of thought -- let's call it Merlin Mann's and Neil Postman's -- that argues that many kinds of work, particularly "creative work," require large, uninterrupted blocks of time. This is a way of working that's intended, I think, to create and maintain a flow state, and assumes that breaking your time into short blocks is counterproductive.

(I’d love to learn a little more about your “outliner.” It looks like a text editor. For a non-programmer like me, it looks dense and difficult to scan. Why do you prefer this over a word processor? Search-ability? Here’s where I’m coming from: I drafted this comment in Word, then pasted it into the comment box on your site. I compose.)

Dave, I'm totally with you on the exercise/time of day dilemma. I certainly have a half-hour free at the end of each work-day to go for a run, but it's the last thing I want to do. I'm engaged in a TTL-type of experiment with this very area right now.

In general, I've observed that my energy level, motivation, and ability to focus decline slowly and then precipitously across my day, with the rate of change accelerating significantly around 3pm. I'm experimenting with breaking the habit of shoe-horning tasks into the 2nd part of my day without regard to this, and instead planning energy-, motivation-, and focus-appropriate tasks instead. The default outcome is quite dreadful -- not only don't I get any "work" done after 3pm, but I feel heavy guilt and despair over it, which fuels more torpor.

Matt, those screen shots really are difficult to read. I'm glad you clarified that you comment in the calendar and not the editor -- that wasn't clear to me (visually or conceptually). It probably doesn't matter much where you do this kind of noting: we've talked before about Natalie Goldberg's advice to throw away your journal when you've filled it; I think cataloging the content is less important for this kind of exercise than developing the habit of reflecting on and extracting lessons from the experience. The habit of self-reflection doesn't necessarily benefit from keeping a permanent record, although writing it down seems to be an essential tool for learning many lessons.

I love your exercise experiment, Greenman. You're a natural TTL-er - we've talked before about this. Re: keeping the journal, that's a really interesting point. The process is absolutely valuable, for me. The test: What would the impact be on your work if you lost the journal? Alternatively, a lot of my capture is "just in case" for the future. If I lost it I'd be OK (as long as I still had my mind) but I think there's a ton of "potential energy" in my log. I've built it up, as it were.

Greenman,

This is a good summary of my condition. Try as I might, exercise will not work for me in the afternoon. A friend suggested mid-day, so I'm thinking about swimming laps during the 12:30pm to 1:30pm time frame. My hope is I'll be re-energized for that 3:00pm-6:00pm stretch of the day that can be so tough.

Thanks for the thoughts guys.

Davey

This is a great experiment example, Davey. Feel free to use me as an accountability partner - I know you have my email. Just send observations if you'd like...

Matt,

I've had success with time blocking. It does help reduce stress and results in a much better finished product. Having discipline not to push it off of your schedule due to other new commitments, as you commented on, is one thing to watch out for.

Different personalities handle this differently. Some can hold themselves accountable while others need to have others hold them accountable (e.g., they need someone to be expecting a deliverable from them). You appear to be able to hold yourself accountable. For those at the other end, perhaps making a commitment to share the "accountability record" you mentioned with someone else each day can help keep these time blocks from being pushed off their schedules.

Gary

P.S., vi rules ;)

Hi Gary,

Different personalities handle [time blocking] differently. Some can hold themselves accountable while others need to have others hold them accountable (e.g., they need someone to be expecting a deliverable from them). You appear to be able to hold yourself accountable. For those at the other end, perhaps making a commitment to share the "accountability record" you mentioned with someone else each day can help keep these time blocks from being pushed off their schedules.

I think you're right - people are motivated differently. I'm pretty much able to hold myself to it, but it's challenging at times. But I'm definitely not the type to let things go too long - not after learning this stuff!

Excellent point re: accountability. It's what I was getting at with [ A Daily Planning Experiment: Two Weeks Of Accountable Rigorous Action | http://matthewcornell.org/2008/05/a-daily-planning-experiment-two-weeks-accountable-rigorous-action.html ]. Thanks for connecting the two.

P.S., vi rules ;)

:-O (For those not in the know, check out [ Editor war | http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Editor_war ].)

Good to hear from you.

Hey Greenman, fantastic comment - thanks a ton.

> Excellent, excellent, excellent!

:-)

> This experiment really effectively pulls together techniques you've discussed in the past

That's a great point; I see what you mean, and I like it.

> You were obviously very rigorous in your execution: outstanding!

It was my stress- and success- management tool. I've now completed 1/3 projects (it went swimmingly), with a new one thrown into the mix - a 10 day deadline. Another block...

> breaking projects down into small parts ... estimating total time, apportioning it by days available, scheduling each part explicitly in your calendar, protecting that time in your day - make all the difference. Without these steps, the deadline can still wreak havoc.

Exactly - a perfect summary. I didn't go into detail, but tried to convey that the planning was pretty rough - a ""back of the napkin"" level, which worked well for this level of project (as opposed to the building ones you mention below).

> there may be more work here than you think - there's almost certainly never less - so it pays to think in an organized way about it from the start.

I've seen this with my clients too. In fact, it came up Tue in a workshop. ""I can't believe I have so much to do.""

> Breaking huge on-site projects into component parts, working backwards from deadlines, constantly re-orienting and re-planning around unexpected developments

I would really love to hear about the tools and techniques you use to do this. E.g., do you require sophisticated software to do this, is there a standard checklist/spreadsheet you've developed, etc. I know you have a lot to say about this.

> Thanks for sharing this, Matt. You've really driven these lessons home.

You're welcome!

> breaking your time into short blocks vs large, uninterrupted blocks of time

Great point. I think they're very compatible. I didn't write about this, but there are different classes of time blocks, with the most general being scheduling regular chunks for ""project work."" This could be writing or painting, or simply putting the nose to the grindstone and working away on your actions. How you use the time depends on the task and the type of work. It may be that sitting in front of a blank canvas for a while is productive for you. Either way, you've made an appointment with yourself that you're committed to honoring.

> your outliner ... text editor... it looks dense and difficult to scan. Why do you prefer this over a word processor?

Yep, it's a hard-core programmer's editor (an extensible system, actually) called <a href=""http://www.gnu.org/software/emacs/"">Emacs</a>, which has a built-in <a href=""http://www.emacswiki.org/emacs/OutlineMode"">Outline Mode</a>. I use it because I can do everything with keystrokes - no mouse - so it's fast for me. It *is* dense and in some ways hard to use compared to a dedicated outliner (even the one in Word), but it works for me.

Back story: I cut my programmer teeth on emacs, jeez, in the 80's getting my BSEE (""C"" programming on a Unix OS), then cemented the keystrokes while doing <a href=""http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artificial_intelligence"">Artificial intelligence</a> programming at NASA late in the decade. We had <a href=""http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lisp_machine"">special computers</a> dedicated to running an AI-friendly language called <a href=""http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lisp_programming_language"">LISP</a>, and I still have very fond memories of working on the <a href=""http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Symbolics#The_3600_Series"">Symbolics 3600 Series</a>. The editor keystrokes are permanently burned in. (Side note: The <a href=""http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Space-cadet_keyboard"">Space-cadet keyboard</a> inherited from MIT research had - get this - seven modifier keys: ""control"", ""meta"", ""hyper"", and ""super"", and three shift keys, ""shift"", ""top"", and ""front"". Combinations of them do the work, e.g., control-meta-c. There are also multi-step command modes... Yum!) I continued using Emacs in <a href=""http://www.cs.umass.edu/"">grad school</a> and stayed with it while programming for 15 years afterwards. Emacs is easy to extend, so it was a natural for the <a href=""http://matthewcornell.org/blog/2005/08/my-big-arse-text-file-poor-mans.html"">Big-Arse Text File</a> I use for (near) universal capture.

I love your comments, Greenman. They always add depth."