What group experiment would you most love to see performed?

Monday, February 7, 2011 at 10:09AM

Monday, February 7, 2011 at 10:09AM I spoke last week with a reporter in London about the Experiment-Driven Life, Edison, Think, Try, Learn, and plenty of important issues around doing self-experimentation. Along the way she asked me what one group experiment would I like to see done if I had a large number of participants. I thought I'd put it to you:

What group experiment would you most love to see performed?

The domain she was interested in was health, but I'd love to hear any of your ideas. The experiment would need to have quantitative measures (at least one) and control and test groups. If you want to get more detailed, here are the questions in the forthcoming Create Group Experiment page from Edison (see tooltips for info):

Experiment Title

Experiment Title - Summary

- Experiment Details

- Requirements to Join

- Instructions for Participants

- Timeline

- Measurements: For each measurement list:

- Name

- Type

- Description

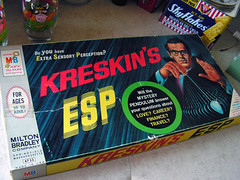

For me, ones near the top would revolve around debunking http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pseudoscience. I think these are ineffectual and dangerous. But in the spirit of true citizen science I'd really like to actually test them. A few possibilities:

- Prayer and health

- Homeopathy

- Astrology

- Fortune Telling, psychics, and precognition

- Traditional Chinese medicine, herbalism, and Ayurvedic Medicine

- Superstitions, such as bad luck resulting from a black cat walking in front of you or breaking a mirror

In the psychology realm I found these possibilities at The Top 10 Psychology Studies of 2010:

- 1) How to Break Bad Habits: The most effective strategy for breaking a bad habit is vigilant monitoring - focusing your attention on the unwanted behavior to make sure you don't engage in it. In other words, thinking to yourself "Don't do it!" and watching out for slipups.

- 2) How to Make Everything Seem Easier: our tactile experience - the sensations associated with the things we touch, might have this same power. For instance, we associate smoothness and roughness with ease and difficulty.

- 4) How to Be Happier: Savoring is a way of increasing and prolonging our positive experiences. Create plans for how to inject more savoring into each day.

- 5) How to Have More Willpower. Our capacity for self-control is surprisingly like a muscle that can be strengthened by regular exercise. Work your willpower muscle regularly, engaging in simple actions that require small amounts of self-control (like sitting up straight or making your bed each day).

- 7) How to Feel More Powerful: the relationship between power and posing works in both directions. In other words, holding powerful poses can actually make you more powerful. If you want more power - not just the appearance of power, but the genuine feeling of power - then spread your limbs wide, stand up straight, and lean into the conversation. Carry yourself like the guy in charge, and in a matter of minutes your body will start to feel it, and you will start to believe it.

Finally, here are some that my fellow Quantified Self blogger Eri Gentry recently came up with:

- How much sleep is enough? Do you feel better when you sleep 8, 9, etc hours? How different is this in other people?

- Have you "developed a relationship" with an infectious disease? For example, do you get a cold at the same time every year - or, do your illnesses have a cyclical effect, changing from summer to winter?

- If you go out in the rain, will you get a cold?

- Is chicken soup an effective remedy for colds?

- Is eastern medicine or herbal medicine effective?

Reader Comments (11)

In terms of something that might go on Edison, what about a meditation study - does meditating in a group vs. alone make a difference to mood/stress levels? I'd be up for that one! :)

Thanks for the great thinking, everyone. Replies follow in line.

@Justin

> What I can envision is a simple directory where anyone can input a hypothesis .. respond with alternative hypotheses .. and .. do self-experimentation and post their results.

> I think something like this desperately needs done .. I would personally volunteer my time (and maybe money) to help make it happen

We definitely need to talk, Jusin. Part of my Think, Try, Learn platform vision is just what you're talking about. I call it DaVinci ( http://thinktrylearn.com/index.php/DaVinci ), and I think of it as both 1) an authoritative level where volunteer experts make sense of a topic's challenges and experiments, and 2) the definitive repository of self-help experiments-to-try. I'll email you.

@Misha

> we as non-trained citizen scientists should adopt a very basic framework like “Observe, Monitor, Improve” or “Explore, Learn, Record”, and then go out and start DIYing.

Excellent idea. I'm partial to "Think, Try, Learn" :-) http://thinktrylearn.com/

> As long as we record things, experts can come along later and make sense of it all. Or, if we get lucky, maybe we’ll make sense of it all ourselves!

A very good point. If the experiments are set up well, and we record quality (and trustworthy data) then anyone who is interested should have access for research and analysis. In this way it combines the best of citizen science the way it's currently used along with new experiments by citizen scientISTS.

@Gary

> Thank you again for a really intelligent, important post.

Thanks! I'm grateful for your having me here, Gary.

> The citizen AS scientist: .. One of the key ideas is peer-review, and by redefining WHO counts as a scientist, science itself is changed. The implications of this are quite big.

Exactly - you've really nailed the point - who counts as scientists. I think we can adapt peer review by inviting a diverse community to participate in experiments, which is what I'm aiming for with Edison. There are roles like experiment designers with academic backgrounds, data surfers who want to do research on what's been done (as Misha points out above), and of course self-experimenters themselves.

I'm happy to take this further if you have more you want to share, Gary.

@Mark

> Dr. Karl, an Australian scientist and science communicator, regularly refers to callers as scientists on his radio show. Just to be clear, those callers are regular people listening to JJJ, Australia’s #1 non-commercial radio station.

Thanks so much for introducing me to <a href="http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karl_Kruszelnicki">Karl Kruszelnicki</a>, Mark. I love the attitude you describe. A find! (More links, FYI: http://www.drkarl.com/blog/karls-blog and http://www.abc.net.au/science/drkarl/default.htm ).

> Collaboration is important for finding discoveries which are important for everyone (or groups of people), but of course individual experimentation is just as important for personal growth.

Yes! The former has not served individuals who have specialized (i.e., non profitable) conditions, and the latter have not been served at all until now.

> So a major responsibility we have is to be as rigourous and detailed as possible (incidentally, this is why I find the QS community so appealing; it’s self-improvement without the vagueness of the majority of the self-help community).

I agree that it's an important goal for some kinds of work, and at the same time I believe there's a role for citizens to adopt a life-as-experiment mindset that doesn't necessarily require quantification. In my case I've received tremendous benefit from this, including managing anxiety and being bolder and happier. It's what my in-process book is about.

> However, as *citizens* (as opposed to professionals/academics), we are doing this because we enjoy it...

Excellent points. I have a "Why do we experiment?" post in the queue, which includes enjoyment, along with others.

> some projects should be left to professionals .. ones ethically sensitive or ambiguous

Absolutely.

> As for other kinds of projects, I think that as long as one has the skills & equipment, an amateur has as much right to do it as a professional (speaking as a PhD student).

Yes - I think we all agree. Well said.

@Rajiv

> Excellent post. I would push even more for the legitimacy of “citizen science” as “citizen-as-scientist”.

Thanks, Rajiv. You're out ahead of the pack on this one, as we've discussed.

> Peer-review, professional affiliations, collaboration, or even the use of statistics … none of these are necessary requirements for good science. Alfred Russell Wallace’s theories on evolution would have been good science even if Darwin hadn’t seconded them. Vladimir Nabokov’s theories on butterfly migration was good science even though it took the formal experts a few decades to accept them.

Yes. Another example that comes to mind is the recent publishing in the Royal Society of an paper by "a group of 8- to 10-year-olds from an English elementary school investigating the way bumblebees see colors and patterns" ( http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2010/12/22/biology-letters-science-j_n_800134.html ). The culture and media absolutely do not promote this. It's funny because just think how many breakthroughs we depend on daily that were discovered by amateur scientists. The example I give in talks is lobsters and medicine - who was the first person who saw a lobster and thought, "Lunuch!" Or think of all the people who bravely tried herbs (and got sick) before they found willow bark ( http://www.umm.edu/altmed/articles/willow-bark-000281.htm )? We are standing on the shoulders of giants, and not just professional ones.

> Given our mutual ex-NASA experience, I don’t wish to minimize the expertise of professional scientists (especially the really good ones), but rather want to stress that thoughtful experimentation and analysis by an individual working alone can be very good science. Which also means I wouldn’t want to automatically rule out anything as being “for professionals” only.

Extremely well put, Rajiv. Thanks for the contribution.

I’d start with the outcomes that I care most about: (1) how can I have the greatest positive influence on others, and (2) how can I improve my relationships.

I posed this question on my blog: How could you change someone’s life in an hour, or 10 minutes, or 30 seconds? That is probably the group experiment I would most like to see – what little things can you do that have the biggest influence on others? Of course there is not going to be a (easy) way to quantify the results, but I think anxiety over measuring sometimes causes us to bypass worthwhile experiments that otherwise could be very insightful. (And I have a degree in statistics, so I am not just afraid of numbers.)

Similarly, I’d like to know what small steps we can take to make the biggest positive difference in our relationships.

Either way, I just want people to start experimenting more—and collaboratively. It is maybe the greatest potential of the Internet, and yet so few people are using it that way.

> Debunking is less interesting to me.

I understand - and like - your point. I picked debunking because I see irrational thinking (something that comes naturally to your species) is harmful. Just look at the conservative movement here in the US that convinces people to vote against their best interests. Debunking claims /through experience/ seems like a way to make a small chink in the armor. Also, they are tired to you (and me, though they're still rich in my mind), but not to those who still hold them :-)

> I’d much rather discover a new, surprising truth

Absolutely - this kind of thing is very exciting to me. The question is how to plant the seeds that might sprout into new insights. The creative process of dreaming up experiments that allow this is special. Seth's "standing on one leg makes me smarter" is a fine example. How did he think of that?

> what little things can you do that have the biggest influence on others

Do you have some specific experiments in mind? I'd love to see people try them as group experiments in Edison.

> not going to be a (easy) way to quantify the results

It would be fun to brainstorm ways to do this. We could always "punt" and simply ask them.

> anxiety over measuring sometimes causes us to bypass worthwhile experiments that otherwise could be very insightful

Yes, and that's a strong TTL practice: Don't let perfectionism get in the way of doing something valuable. Thanks for reminding me.

> (And I have a degree in statistics, so I am not just afraid of numbers.)

That might have been a mistake to tell me. I'm going to ask to use your brain for Edison 3 - the statistical recommender engine :-)

> Similarly, I’d like to know what small steps we can take to make the biggest positive difference in our relationships.

Do you know about the book <a href="http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0761129235?ie=UTF8&tag=masidbl-20&linkCode=as2&camp=1789&creative=9325&creativeASIN=0761129235">One Small Step Can Change Your Life: The Kaizen Way</a>? You might find it helpful.

> Either way, I just want people to start experimenting more—and collaboratively. It is maybe the greatest potential of the Internet, and yet so few people are using it that way.

Well put. That's exactly what I'm trying to do. How's this for a beta tagline: "A simple tool for people to create and run solo and group experiments in a community of fellow citizen scientists."

Re: the tagline, I think it’s good as a clear statement of what your product is, but I’d say probably lacks the meaningful or inspiring kick you’d hope to get out of a tagline. We can talk more about this.

By the way, I think the name Think, Try, Learn is perfect – I think that really nicely embodies the whole process.

You asked two questions that I think kind of answer each other. One is how do we find the creativity to come up with Seth Roberts-like ideas, and the other is whether I have examples of small steps that could have big influence. I do have some examples in mind, but I think rather than starting with one of my examples and using that as a group experiment, I think it’d be better to start with the broad question (“What small things could make the biggest difference in someone’s life?”) then have people share their own ideas. That social exchange (idea sex, if you will) is, I believe, how creativity most reliably happens.

In other words, I think the ideal process is to start not by testing a specific hypothesis, but by asking a broad question and then bringing a bunch of hypotheses to the table. Only then do you start weeding through hypotheses and testing them in measurable ways.

(And as for examples, here is one that I’ve been thinking about a lot lately: I think one of the most powerful questions you can ask someone is something like, “What babystep can you take right now that would most improve your life over the next 6 months?” I suspect that just getting someone to think about that for a minute could potentially go a really long way.)

One thing that springs to mind for a large group and on the social end of things are the utilitarian societies that 19th century people were promoting. Was it Lovejoy that had one? You would need a large group to try a social experiment like this because most societies rely on specialization in order to acccomplish tasks that benefit the society. Like maybe only one in 300 people are doctors or a dentist or specialist like that. You dont need that many more.

The use of internet offers a greater amount of technology/communications that those guys had in the 19th century. What can you do with this? THink of our legal system: could a society exist with its own laws and understandings adn operate a legal system better than those found in modern countries?

What about the very nature of countries/states themselves? I guess it was one of the Roman emperors (Diocletian?) that declared alll the people belonged to certain farms and cities and such. Once a state can identify a person with a physical location, then that person is basically doomed to be a pawn of that state. Modern states operate not much differently do they not? Everyone has an address, everyone is tied to their state. But wha of internet societies? Could such a society exist and regulate itself free of the geographic boundaries that are implicity in conventional nations/states?

See? I think you have to aim higher than merely debunking with this social experiment stuff.

> tagline ... lacks the meaningful or inspiring kick

I agree. Thanks for the feedback, Justin.

> By the way, I think the name Think, Try, Learn is perfect – I think that really nicely embodies the whole process.

:-)

> start with “What small things could make the biggest difference in someone’s life?”) then have people share their own ideas. That social exchange (idea sex, if you will) is, I believe, how creativity most reliably happens.

Very good point - In fact, it's what I did with this post, but one level more specific (i.e., in the context of small change that could make a big difference). We should talk about nudges, Justin. ( http://nudges.org is a cool idea, BTW.)

> ask a broad question and then bringing a bunch of hypotheses to the table

I understand. But do you think that's what Seth did with his stand-on-one-leg hack? I think that having a lot of inputs is key - inspiration and ideas coming from diverse sources. That's one part of Edison I hadn't thought of before - thanks! (Some cross-fertilization in action. :-)

> “What babystep can you take right now that would most improve your life over the next 6 months?”

I like it, and I also wonder how they'll know. For me, it's sometimes not until I see something outside my current thinking that I get inspired.

Great conversation, Justin. Let's mine this for DaVinci ( http://www.thinktrylearn.com/index.php/DaVinci ) ideas.

> Well the thing with debunking is, why would citizen experiments or any sort of large group be any more useful for this than conventional experimentation?

Why, results, of course! My hope is that seeing would be proof, not just believing. Depends on minds being open, but those are the folks who would be attracted to Edison in the first place, I think.

> utilitarian societies of 19th century .. Lovejoy

Not surprisingly, this is the first I've heard of it. I found http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Utilitarianism and this: Chapter Four, Utilitarianism, Laissez Faire and Individualism ( http://www.weisbord.org/conquest4.htm ):

> Under Hume, the Utilitarian school was founded. According to him, all that we knew were our senses. We acted to obtain pleasure and to avoid pain according to our selfish needs. We experimented to find out which experiences would bring us the greatest good. And that law was the best which brought the greatest happiness to the largest number of people. All ideals were here dissolved into a sensationalist, sensualist approach in which the only binding nexus was self-interest and cash payment. In this way Liberalism tried to justify its rule, not from the aspect of good morals, but from the angle of whether it paid good dividends. The entire emphasis was placed on individual egotism.

Is this the right person? http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthur_Oncken_Lovejoy

> You would need a large group to try a social experiment like this because most societies rely on specialization in order to acccomplish tasks that benefit the society. Like maybe only one in 300 people are doctors or a dentist or specialist like that. You dont need that many more.

I don't follow. I understand the power of numbers. Are you saying that specialization takes away the need for personal experimentation?

> could a society exist with its own laws and understandings adn operate a legal system better than those found in modern countries?

Jeez, I have no clue. Maybe it's time for you to write some of this up!

> But wha of internet societies? Could such a society exist and regulate itself free of the geographic boundaries that are implicity in conventional nations/states?

What about a geography of ideas? But maybe what we have on the net is a geography of *beliefs*. Fox News folks congregate in their echo chamber, for example, where the state of discourse has one dimension: Sound volume. (Not to pick on Fox. OK, to pick on them :-)

> See? I think you have to aim higher than merely debunking with this social experiment stuff.

I stand by debunking as a fantastic starting point :-) But better yet, give me some specific experiments!

http://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/amana/utopia.htm

The thing with debunking is, it may be a waste of resources to devote a large group of people to a project that can easily be achieved with one insightful researcher. I really dont see how putting many people on the debunkign project makes it more efficient.

in contrast, you would need a large number of people to create a utopian society because with increasing specialization a small number of people would probably not be able to function very effectively. Say 50 people try to start a utopian society, you immediatel run into problems of "who can fix a carburetor?" or "who can fix teeth?" Right? So a large population would be required to carry on a social experiment like that. That would be a benefit of having a large number of people in on it. I dont see the same sort of value in numbers with a debunking experiment.

that is all I was saying. I freely confess to having worded that awkwardly