[Cross-posted to Quantified Self]

We experiment on ourselves and track the results to improve the way we work, our health, and our personal lives. This rational approach is essential because there are few guarantees that what works for others will work for us. Take the category of sleep, for example. Of the hundreds of tinctures and techniques available, clearly not all help everyone, or there would be exactly one title in the sleep section of your bookstore, called "Sleep," and no one could argue about its effectiveness. Treating these improvements experimentally, however, requires a major shift in thinking.

We experiment on ourselves and track the results to improve the way we work, our health, and our personal lives. This rational approach is essential because there are few guarantees that what works for others will work for us. Take the category of sleep, for example. Of the hundreds of tinctures and techniques available, clearly not all help everyone, or there would be exactly one title in the sleep section of your bookstore, called "Sleep," and no one could argue about its effectiveness. Treating these improvements experimentally, however, requires a major shift in thinking.

But being human isn't that simple. There are variables and confounding factors that mean you have to take matters actively into your hands if you want to really know what's personally effectual. That's why what we do here is so exciting. Instead of accepting common sense, we take a "prove it to me" approach and work to find out for ourselves. Operating from this basis, rather than faith, is more effective in the long run. (It's why we use science to understand the world, rather than astrology or phrenology, for example. Just look at what we've accomplished.)

As I tried to say in Making citizen scientists, this is heralding a move from citizens-as-helpers to true citizen scientists - people who get genuinely curious about something and decide to test things out for themselves, rather than simply trusting what others say will work. If we expand that vision five or ten years in the future, I think there could be a major shift in how we search for ways to improve ourselves, and that's what I want to share here.

Picture that you have something you're trying to change, and you want to find starting points, especially what's worked for others. Ideally you know someone who can point you in the right direction (medical professionals come to mind), but rarely do our social and professional circles cover everything we want to improve. Normally we are on our own, and must sit down and courageously cast ourselves into the vast sea of the web. What do we find? An insane number of hits mysteriously organized by clever algorithms. Again, take sleep. My search for insomnia yielded over three million hits. How do we decide how to use these results? I think the fundamental issue is of trust. How can I trust what I read if there is nothing backing it up? Google is great for some things, but for self-improvement, what I want isn't necessarily what's popular (let's face it, the popular kids at school weren't necessarily the smartest - spoken from experience). What I want is something that's a reasonable starting point. That is, something that has a high likelihood of yielding useful information that moves me quickly in a helpful direction. (My scientific colleague calls this exploring the "search frontier.")

Instead, what we have is a immense collection of definitions, blog posts, news articles, how to's, marketing literature, product reviews, fringe nuttiness, and the like. In other words, a Wild West of self-improvement. Exciting, dangerous, risky, unproven, and loaded with potential.

What's closer to what we want are the discussion board threads and blog comment exchanges where people shared what they tried and what has and hasn't worked. After a quick search, two examples that came up in the sleep realm are at talk about sleep and iVillage. However, we have three problems. First, my search for insomnia discussion boards still generated almost three million hits. That means we don't know where the quality work is taking place. Second, and far worse, is that the way people have gone about their search for solutions is rarely principled. This is because applying a scientific approach to self-help, as I tried to explain above, is still rare. (Want to test that? Just try to tell someone why you're reading this site, and watch the confusion on his face. "You're tracking what? But WHY?") With questionable methodologies come questionable results. Finally, if there truly are well-run experiments, they are scattered throughout the site on various threads, the data is not likely in a form we can analyze, and it's very hard to find who else has tried the experiments and what they discovered. In other words, the knowledge, experiences, and results of everyone's hard work isn't structured or centralized. And that's a massive waste.

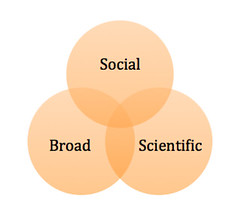

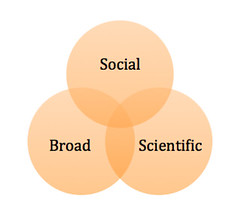

Now imagine that there is a community of self-experimentation tools that meet the three characteristics I outlined in my experiment-driven life talk (my original post is here): Broad, Social, and Scientific. On these sites will be records of millions of past and in-progress experiments being performed daily by thousands of citizen scientists, both individually and collectively. They will be structured to expose what folks did specifically, how the process went for them (in some ways as important as results themselves), what the data was, and how they interpreted it. And they will have targeted search tools to find experiments in a variety of ways - topic, treatment type, ratings, etc.

Visualize yourself going to one of those sites and searching folks' work for your topic. Assuming they're structured reasonably, you could find something marvelous: Actual personal experiments, around your situation, with their data and conclusions. Wow! This should allow you to get a summary view of the things people have tried, who else tried it, and what they learned. In other words, it would be a data-driven entry to deciding what I should start trying.

Ultimately, I envision this moving towards a kind of personal development "general store" where instead of facing an intimidatingly large self-help section in your bookstore (i.e., the big-box help-yourself model), you come to a desk with one person sitting and asking, "How can I help?" You tell her your topic and a little about yourself, then ask for advice. The clerk, who has read all of the books on the subject, answers, "For someone like you, the most effective experiments were ..." and lists five or six to look at. I think of it as a kind of intelligent, experiment-based search engine that factors in personal data, demographics, and topic (maybe as simple as keywords, for starters) and serves up ballpark suggestions.

What do you think? My ideas are still developing, so this is still a little rough, but I honestly believe we could build such an ecosystem. Are you with me?

Wednesday, September 7, 2011 at 9:18PM

Wednesday, September 7, 2011 at 9:18PM