[I am pleased to share this guest article from Edison user Ralf Westphal, who blogs at http://ralfw.blogspot.com. This is a result of my experiment to offer Edison users a chance to share their thoughts on the Experiment-Driven life. I invite you to consider his point that our lives are complex systems, ones that cannot be represented as simple state machines, and which can only be modified via experimenting. For these kinds of systems, cookie-cutter solutions don't apply (this is my point about books on success - they aren't repeatable), and thinking things through will only take you so far; you have to steer. I also like his ideas on experimenting with blondes. I've not done any editing, just some formatting. Thanks Ralf! -- matt]

[I am pleased to share this guest article from Edison user Ralf Westphal, who blogs at http://ralfw.blogspot.com. This is a result of my experiment to offer Edison users a chance to share their thoughts on the Experiment-Driven life. I invite you to consider his point that our lives are complex systems, ones that cannot be represented as simple state machines, and which can only be modified via experimenting. For these kinds of systems, cookie-cutter solutions don't apply (this is my point about books on success - they aren't repeatable), and thinking things through will only take you so far; you have to steer. I also like his ideas on experimenting with blondes. I've not done any editing, just some formatting. Thanks Ralf! -- matt]

You think life's complicated? How then can you find out what to do? Well, I'd say think harder before you decide about any matter. Read up on the subject, talk to people who seem to be knowledgeable about the topic of relevance, consciously employ a decision process like the Analytic Hierarchy Process [1]. Then, in the end, after an acceptable amount of analysis, deliberation, and musing... decide and act accordingly. There'll be a good chance the outcome will be as expected.

When matters are complicated, thinking will help. Through more thinking it will become clear, what to do to achieve a certain outcome. For complicated systems thinking and analysis/decomposition will uncover the actions to be taken to move the system from its current state to the desired state. And having operated a complicated system will make you an expert; that means you become more and more efficient in directing the system from state to state. You'll need less thinking and can rely more on intuition.

Complicated systems are fundamentally predictable. If you know their current state you can "calculate" their resulting state for any given change you are going to apply. The "calculation" might be hard, very hard, but that does not matter. As long as there is some way to "calculate" state transitions a system is just complicated.

Take the Tower of Hanoi [2] or Rubik's Cube [3] for example. To solve those games you just need to think according to their rules.

Take flying an airplane as another example. Moving thousands of tons through the air can be done by a computer. Millions of people trust auto-pilots every day - while you personally might think you could never do it. But it's not magic. For sufficient computing power there is enough time "to think" about what actions to take according to the airplane's current state and current sensory input.

Or is this complicated? It seems to be since a computer can do it, and computers are good at doing rote calculations.

In fact, though, flying an airplane is a complex matter. The combined system of airplane and environment is complex. Flying an airplane is a steering problem, like driving a car is, or riding a bicycle.

Systems are complex, just thinking and analysis does not clearly tell you, which actions to take to move the system from its current (macro) state to the desired (macro) state.

Now, think again about your life. Do you still think life's complicated?

No. Life is a complex system. Except for matters like untying a knot or cooking pasta life is complex: You don't know what the outcome of your actions will be. And thinking hard about a matter of your life will rarely lead to a surefire plan.

Of course, people want their life to be at most complicated. Carrots-and-sticks management is an example of that. A manager incentivizing an employee is trying to push a button to reach a certain result. The reasoning is, "If I give her X, then she'll accomplish the task in a shorter time." That's linear thinking. That's thinking in clear cause effect relationships. However, thinking like "This action will certainly lead to that outcome" is at most working in complicated scenarios.

The world in general and specifically people don't have clearly labeled buttons to push, though, or levers to pull to move them from current state to desired state. Will the employee really accomplish the task in a shorter time just because of the incentive? Maybe, maybe not. It depends on the kind of task - working in a quarry or developing a business plan -, and it depends on the kind of bonus - money or time off or a medal - which means it depends on something largely unknown: the state and personality of a living system. Some people can be motivated with money of a certain amount - others not. You never know, at least today. And that's just a small facet of life's complexity.

How about losing weight? What about opening a bakery store called "Our Daily Bread" in New York, offering all sorts of German bread and cake, of course sold by blond girls wearing traditional German Dirndl [4] dresses and speaking with a lovely German accent? Or take flying an airplane as an example again.

How do you go about it? How do you reach your goal of losing 10 pounds or becoming New York's most trendy bakery or safely transporting 250 people from Chicago to L.A. through the air?

Well, you start experimenting. Experiments, lots of experiments are the only way to move a complex system from a current (macro) state to the desired (macro) state.

There is no recipe for losing weight (and not gaining it back soon after) - otherwise somebody would have already become extremely, no, humongously rich by selling access to it. So what you have to do is try something and see what happens. Should you eat more salad and less fat? Nobody really knows. You have to see for yourself. Devise an experiment and faithfully execute it like any scientist would do. Then check the results, compare them to your hypothesis, and either continue along the path of success or change your course by modifying hypothesis/experiment and trying again.

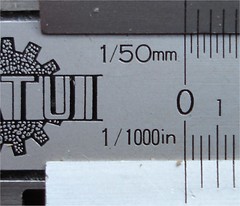

The same goes for opening a bakery in New York. Which part of New York to open it in? Ask market research. Thinking will be of quite some help to find the right location. But should the girls behind the counter really wear traditional German dresses? Do they need to be blond? How many different sorts of bread should you offer? What's the right price to a piece of Sachertorte [5] or a loaf of Vollkornbrot (see [6] for a picture of typical whole-grain bread)? You simply don't know. You have to try and see what happens. Formulate a hypothesis like "Young blond girls traditionally dressed will make a difference in sales" and then run an experiment. Make it small so falsification of your hypothesis won't kick you out of business. But nevertheless experiment. Take small steps, move forward incrementally towards your goal.

That's also called steering. For a given (macro) state "calculate" a new intermediate state in the direction of your ultimate desired (macro) state, take action to move to the new state - then check if you reached it and if you still feel en route to your goal. Chop the complex journey from here to your goal into just complicated little steps. That's what an auto-pilot is doing. That's what a computer is capable of doing. Flying a plane is not like shooting a cannon ball. Shooting is complicated; its outcome can be calculated. By flying is complex. Since a (auto-)pilot does not fully know the state of an airplane's environment he can only make small adjustments and watch what happens.

Life's a complex endeavor. The only way to reach whatever goals you have is by continuous experimentation. That's what you've been doing anyway and can be called learning. But why not take it to the next level? Why not switch to a more explicit experimentation mode? Why not more consciously formulate goals and hypothesize about how to reach them and then try moving towards them in small experimental steps. Think, act, reflect - or as Matthew Cornell phrases it: think, try, learn.

Viewing life as a multitude of ongoing and ever changing experiments is a road leading to more satisfaction. It replaces the fixation on goals with a process. And this process can never fail. So if you refocus on faithful experimentation you're in for a lot of happiness. Because success for an experiment is defined by just producing a result. But how can your experiments not produce any results? Either they support your hypothesis and you're happily right on track towards your goal; or they falsify your hypothesis and you can be happy to know so you can change your course.

An experimenter's life is a happy life. So why not start thinking, trying, learning today to tackle life's complexity?

Endnotes

Friday, January 14, 2011 at 8:51AM

Friday, January 14, 2011 at 8:51AM