12 Myths about Self-Tracking

Saturday, February 12, 2011 at 8:25AM

Saturday, February 12, 2011 at 8:25AM [Cross-posted to Quantified Self]

(Let me get a little provocative this time around and share some myths of self-tracking I've been playing with. I'd love to hear your thoughts about these and any other myths you might know about.)

Myth: You have to use technology.

Fact: A good guideline is to use a tool that's appropriate for the job. I know people who get good results using spreadsheets, and paper has some wonder affordances. (Read Malcolm Gladwell's The Social Life of Paper for a fascinating analysis of air-traffic controllers' paper-based system.) Then again, with large sets of data, visualization tools are invaluable.

Myth: Not everything can be measured.

Fact: I suggest that, with a little (or maybe a lot) of creativity, you can come up with something you can measure for any experiment. Check out Alex's post, How To Measure Anything, Even Intangibles. (Bonus: Do you have any that are giving you trouble? Let's play "stump the blogger!")

Myth: You have to be a scientist.

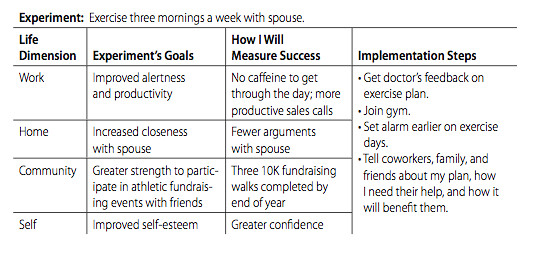

Fact: While it probably helps to have a background in science, and better yet one in statistics, we can still do valuable work with rudimentary skills, given you design a strong experiment that can teach you something.

Myth: You have to start with a goal or theory.

Fact: Sometimes we aren't to the point where we have a working theory, but we are ready to start poking and prodding to see what might emerge. However, I'd argue that, at a minimum, we should always start with a question. What you ask might change, but it'll get you moving. I'm still a believer that simply observing keenly can lead to awareness and eventually change.

Myth: Data-tracking is cold and dispassionate.

Fact: Far from it! Just think back to an experiment of yours where you had an insight or surprise - how exciting was that? Curiosity is an emotion, after all, which drives our love of exploration, adventure, and discovery. Plus, exploring the world with a curious mind is great fun. At the same time, it takes a level of detachment to see results for what they are, especially if they rub up against something that we are attached to.

Myth: Self-experimenting is just for problem-solving.

Fact: While addressing a specific concern is an excellent application of the self-quantification, I think of it more as a life-encompassing mindset. That is, a perspective on how to go about our lives, and one that asserts that our job of learning is never done.

Myth: Self-experimenting is easy.

Fact: I'm sure you've noticed that it takes discipline to consistently track things about your life, and to do the thinking and learning that results from your data. Key is a strong desire to learn something and, ideally, to get an answer.

Myth: Self-experimenting is hard.

Fact: The other side of the coin is that our work comes down to something simple: Thinking of a change to make, trying it while making observations, and then learning via reflection. Start out with something small that's easy to measure, and then work up from there.

Myth: Citizens can't do science.

Fact: This one is about the broader view of the validity of citizens doing science, and was what I was getting at in my post Making citizen scientists - that this work applies especially well to the individual. (For some reasons, see the excellent comments at the bottom of that post.) Related to this are two other myths, the sample size of one is not valid and the results need to be clinical-grade ones.

Myth: It's just for external things.

Fact: Some of the richest territory to mine via experiments is your mind, behaviors, and mental models. Treating your thinking and behavior themselves as data is valuable, and can lead to fresh insights that you can use for improvement.

Myth: You have to use numbers.

Fact: Scandalous, I know, but I've found that in some cases I can test out ideas without having to measure anything. However, I always make entries in my experimenter's journal, which keeps me engaged and gives me something for later analysis.

Myth: It only applies to health.

Fact: Related to my point above about the experimental mindset, I've had a lot of benefit from applying the thinking to all parts of my life. While health is the number one category in Edison, there are lots of other creative applications, including the social and work realms.