The Experiment-Driven Life

Thursday, June 24, 2010 at 6:01PM

Thursday, June 24, 2010 at 6:01PM In his seminal article The Data-Driven Life, Gary Wolf [1] introduces us to the field of personal informatics and summarizes the self-tracking movement to date [2]. I was excited to discover this piece because it touches upon concepts I've been experiencing, collecting, and brewing for the past five years.

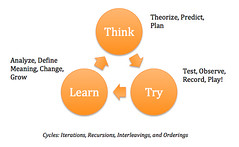

Wolf approaches his main point - that self-tracking is a tool of self-discovery - by covering what I've extracted as four main areas: General points, Science, Personal development, and Social aspects. Below you'll find my bulleted summary of them (read the full write-up if you have time) followed by how we see our Think, Try, Learn (TTL) work neatly binding together his data-centric ideas into a new way of looking at the world, that of a scientifically-oriented life as experiment. My thinking here is a work in progress, so please, share your thoughts.

Central ideas

General points

- Humans have blind spots and make decisions with partial information. A better alternative is to use data.

- Early adopters have started measuring in earnest and using experiments. This "pathology of quantification" is (currently) considered abnormal.

- Data has value: It facilitates tests, comparisons, and experiments; it increases awareness and the feeling of self-mastery; and can lead to insights and change.

- Quantitative data is best, rather than a journal or therapeutic talk.

- The process is to start with a question, gather data, "live by it," and repeat, possibly with newly-discovered questions.

With respect to science

- Most self-exploration is not principled. Better is to gather data, record dates, toggle conditions, and keep careful records of outcomes.

- Personal experiments are not clinical trials. Instead the goal is understanding and improving yourself, not the entire species.

- Measuring and then changing conditions is different from anecdotes. The former is more like science and goes to testing a theory.

- General knowledge never applies perfectly, so self-tracking is valuable for individual applications.

Applied to personal development

- Human behavior is mysterious, and our reasons for doing things are opaque.

- Applying self-tracking to personal development is new, but becoming popular.

- Our lives generate much data.

- Goals are often unknown. Some people start with questions, but most trust that data has value and might lead to unexpected questions.

- Data tracking reduces emotional qualities (e.g., shame) and increases intellectual/rational ones.

- A central hypothesis is that many problems come from lacking instruments to understand who we are.

- Technology (especially mobile phones) makes numeric tracking easier and more attractive.

- Beware bad science (biases), but intentionally ignoring data is useful (e.g., can lead to forgiveness).

- Beware tying self worth to data because it can lead to judgement, etc.

Social aspects

- Social media makes data sharing encouraged and accepted.

- We like to share, and having data makes sharing natural.

- Sharing affords opportunities to help.

Toward a cohesive framework

Wolf covers a lot of ground, and all of his points are important. At the same time, we think they could benefit from some unifying. To address that, we see two main areas missing from the discussion: a true scientific perspective that encompasses personal tracking, and a comprehensive social platform that supports meta conversations as a central part of our experiments.

Let's look at these in turn.

A scientific method for personal development

While recording and tracking personal data is an important and natural first step, it's only one part of what needs to be a more scientific process. Our Think, Try, Learn work aims to do just that: pull current data-centric approaches together into a new philosophy of life - a kind of personal science that organizes the act of observation (the true role of collecting data) into the larger life-as-experiment perspective. In other words, to move us from a data-driven life to a wider experiment-driven one. We've started putting these elements together into our book [3], but let me share a few of the concepts as they relate to Wolf's piece.

- Method: As pointed out, we need a personal scientific method, but we've found that applying a rigorous interpretation [4] to individual improvement presents significant challenges, such as forming concrete theories, repeatability, and the "N = 1" problem [5] to name a few. While studying this we've discovered a simpler version that works well - what we call the Think, Try, Learn cycle (see the process diagram above). It encapsulates the spirit of the method without turning away people who have little scientific background but could still benefit from the perspective.

- Mindset: Looking at everything you do as an experiment takes a shift in thinking, such as the definition of success, what failure means, and roles mistakes can take. Important concepts include asking questions (vs. having answers), keeping our eyes fresh (vs. biased filters and "expert mind"), and cultivating a healthy sense of detachment (vs. being attached to particular outcomes). "Baking" this into a culture is an opportunity and a challenge. To that end, in addition to the book, something we're currently trying in Edison (our TTL experimenter's journal) is to get our users thinking about this approach from the start. We do so by asking leading questions that people answer when creating new experiments:

- What will you do?

- How will you test your idea and measure success?

- How will you know you are done?

- How will you enjoy the journey?

- Practices: Knowing a method and putting it into practice are different dimensions, and they must be integrated to be effective. We are looking at things like how to work the TTL cycle, keeping the process agile ("test often and fail fast" as Pam puts it [6]), and of course rigorous observation and capture using techniques and tools like Wolf describes.

- Process: Many tools focus on the data itself (product), rather than the act of collecting it (process). However, important growth and character development happens during experimentation, in some cases overshadowing the result. This explains why we think personal informatics sites without user commentary don't capture the data's greater context. After all, this is where our stories [7] are created, encouraged, celebrated, and shared.

- Enjoying the ride [8]: As Wolf points out, there's a risk of getting too caught up in self-measurement. For balance, it's ideal to take pleasure from what we try. No philosophy is complete without addressing this, so how do we enjoy the experimental process itself? TTL practitioners do so via the acts of paying attention, staying curious, relishing discovery, being playful, cultivating a sense of humor, and celebrating. Lest you think science is all seriousness, I like Lewis Thomas's observation that you can tell when something important is going on in an experimental lab by the laughter.

- Collaboration: The best learning takes place with the help and wisdom of others, which makes it crucial to create a network of fellow experimenters. More on this next.

- Lifelong learning: Finally, science should be a lifelong discipline - something we integrate deeply into our lives and work to master. Even when you fail to reach a goal you can always be successful at "being excellent at discovery" (as one TTL practitioner put it). This is the essence of what Wolf calls "our quest to figure ourselves out." How rich that is!

A comprehensive social media for experimentation

Along with a scientific method for personal development, we need a social platform that captures not just data, but something possibly more important: the conversations about the experimentation process itself. It can be argued that this is where insight actually takes place - where lessons are learned and character is built.

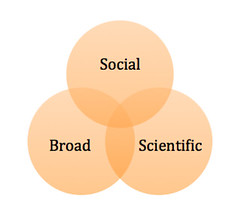

Regarding existing self-tracking sites (of which Wolf mentions many), it helps to think of three dimensions (see the diagram to the right):

- Domain: A range of topics from the highly specific (such as your sex life or mood) to virtually anything in your life (such as DAYTUM or FlowingData's your.flowingdata).

- Philosophy: A scientific range from pure observation (Nicholas Felton is a master) through personal experiments (I have no good examples; maybe CureTogether?) all the way up to clinical trials (PatientsLikeMe).

- Context: A social range from individual to group.

We think the sweet spot, which hasn't yet emerged, is the intersection of all three dimensions. That is, a platform that is broad, social, and scientific. As mentioned above, Edison and the eventual TTL Platform are our first baby steps in that direction. (Yes, there's a lot of work ahead, but we're trying to live the TTL principle of start small.)

Summary

To wrap up, we believe the exploding self-tracking movement is an exciting step in the broader direction of a personal scientific philosophy - one that leverages the set of techniques developed over the last 400 years that have given us the most powerful way to approach the unknown: science. The technology that supports this should be a software platform that tightly integrates the this experimental perspective into a social tool that spans collaborative investigations across all domains. This, we argue, could move us from a data-driven life to an experiment-driven one. And how amazing would that be?

References

- [1] Wikipedia entry, his company AETHER, and his Quantified Self work.

- [2] Other influential articles on the personal informatics movement include The New Examined Life by Jamin Brophy-Warren, Wolf's Wired article Know Thyself: Tracking Every Facet of Life, from Sleep to Mood to Pain, 24/7/365, and Matt Jones's presentation Polite, Pertinent, and... Pretty: Designing for the New-wave of Personal Informatics.

- [3] Tentative title: "Think, Try, Learn: A scientific method for discovering happiness."

- [4] The steps typically mentioned when talking about the method are something like the following. Typically not all steps occur in every case, and sometimes they are out of order.

- Make an observation.

- Ask a question.

- Formulate a hypothesis.

- Make a prediction, which will explain our results.

- Conduct an experiment.

- Analyze data and draw a conclusion.

- Repeat the work.

- [5] Small sample size. It's too complicated for me, but my academic colleagues know the details, and ways around this. These will be crucial when we start running trials on our platform.

- [6] This is from Pamela Slim's fine book, Escape from Cubicle Nation: From Corporate Prisoner to Thriving Entrepreneur.

- [7] I wonder if a useful measure of a full life is the number of stories we create and participate in. Fortunately, we believe that all experiments generate stories. For example, who wouldn't want to know about implanting a magnet in your finger or going into a job interview cold turkey?

- [8] I first encountered the phrase in Patricia Ryan Madson's book Improv Wisdom: Don't Prepare, Just Show Up (maxim #13).